Spoleto

FRANCIS was the son, of Sante Possenti, a lawyer of great talent, who was appointed Governor of Umbria, in Romagna, Italy, when barely twenty years old, and who, before retiring from public service, became Grand Assessor of Spoleto. Francis mother belonged to one of the best families of Civitanova, in the Marches. Both father and mother were distinguished, not only by birth and position, but also for their piety and Christian virtues.

Francis was the eleventh of thirteen children. He was born at Assisi on the first day of March, 1838. His father had not yet been made Grand Assessor of Spoleto. The child was baptized on the day of his birth, at the same font where, over six hundred years before, another Francis, the great patriarch of the city and glorious saint, was baptized.

Before he was quite four years old Francis lost his pious and beloved mother. Four of her children had died before her. Signor Possenti, though stricken with grief at the untimely death of his tender and affectionate wife, neglected neither the important duties of a governor nor the responsible obligations of a father. He entrusted the management of his household, as well as the care of his nine children, to a responsible and experienced lady named Pacifica.

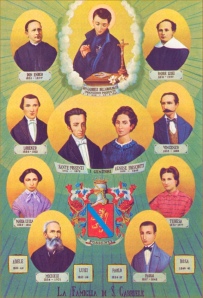

The Possenti Family

The education of Francis was begun by Pacifica, a tutor, and his pious father. On the whole, he was a good boy, but in these early years he manifested very few signs of the sanctity for which he was to be so distinguished in after years. He was, if anything, the gayest and liveliest of the family. A proneness to anger, levity, and disobedience was his principal fault. When corrected by his father, his unruly temper would reveal itself by his inflamed face, and by the abrupt manner in which he would leave the company. But his anger would cool as quickly as it had heated, and in a few moments he would return in tears to beg pardon of his father. His tutor, Philip Fabi, a young cleric of piety and learning, had by no means an easy task. In his childhood Francis was changeable and fickle. At one time he would be full of fervour at his studies and religious duties, and at others careless and indifferent. His tender sympathy, however, and his loving kindness made him a great favourite with his brothers and sisters at home, and with his playmates elsewhere. Hardly had he come to the use of reason before he began to show a marked thoughtfulness and friendship for the poor. He would deny himself to give to them. The charitable Pacifica could not always satisfy the demands he made upon her for those in need. To her objections Francis would answer: “Why! Father wants us to be charitable; we ought not to despise the poor, for we don’t know what we may one day be ourselves.”

THE education of Francis, begun by his father, Philip Fabi, and Pacifica, at home, was continued by the Brothers of the Christian Schools, and finished by the Jesuit Fathers at Spoleto. Sante Possenti assumed the office of Grand Assessor there in 1842, about the time of his wife’s death.

At school Francis quickly made himself a favourite with both companions and teachers. He was brave and outspoken. To the suffering he was a warm-hearted sympathizer; to the weak and persecuted, a fearless champion; to companions, a staunch friend; and to masters, a willing and talented pupil. In those days few prizes were given at school, but Francis was the winner of more than one.

His professor in mental philosophy said that he was one of his aptest scholars. He was selected as public reader, both for the sodality at the college and for the catechism class held in its church on public festivals. At the public exhibitions of school and college the most difficult parts generally fell to the lot of our hero.

Francis finished his public school course at the Jesuit College at the age of eighteen years. He entered society before he left college. The fickleness of mind that had manifested itself in his childhood appeared again from time to time in his early manhood. It was revealed by his manner of dressing. For a time he would be so fastidious in dress as to become almost foppish, and then again he would take little heed of style or fashion. He indulged rather freely in novel-reading and theatre-going dangerous pastimes for one of his years. Francis afterwards referred to the risks to which he had exposed both mind and morals by indulging these tendencies. After entering the monastery he wrote to a friend:

“Dear Philip, if you truly love your soul, shun evil companions, shun the theatre. I know by experience how very difficult it is, while entering such places in the state of grace, to come away without either having lost it, or at least exposed it to great danger. Shun pleasure parties, and shun evil books. I assure you that, if I had remained in the world, it seems certain to me that I would not have saved my soul. Tell me, could anyone have indulged in more amusements than I? Well, and what is the result? Nothing but bitterness and fear.”

Yet neither Francis brothers and sisters, nor his companions at school, ever saw anything very reprehensible in his conduct. He was regular in his religious duties, never neglected his morning and evening prayers, and assisted daily at the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass.

Sante Possenti’s talents and honourable position gave him a high social standing, and his son could move in the best society of Spoleto. Francis found the doors of all the leaders of society there open to him. He kept them open, and won a hearty welcome for himself wherever he went by his accomplishments and winning ways. He was fond of music, and could always contribute a fair share to the evening’s entertainment. He was fond of the dance. Handsome in person and graceful in movement, he was always an acceptable partner. He was fond of the theatre, and could always take a leading part in private performances. He was successful at college; he was successful in society. Everyone said that he would be successful in whatever he undertook, and that a brilliant career lay before him in the world.

The day that closed his college course was a day of triumph for Francis. Handsome appearance, graceful address, expressive gesture, command of language, and good voice had gained for him first place among the young men of the Jesuit College. He was chosen to deliver the opening discourse at the commencement exercises. A brilliant audience of learned and aristocratic men and women were assembled in the large hall. A friend of the young orator for the occasion has left us a minute description of him as he stood on the stage.

“His clothes, ” he says, “were unusually elegant; a matchless and richly folded shirt-front adorned with jewels; bright buttons on his cuffs; a silk cravat around his neck; his hair studiously parted. Add to these his white kid gloves and patent-leather shoes, and we have a pen picture of young Francis Possenti as he stood, smiling and serene, facing his many friends and the distinguished audience about to be pleased spectators of his triumph.”

The audience was delighted with his address. They loudly applauded and cheered when he was presented with a gold medal for excellence in all his studies.

Those who gazed upon and cheered the handsome youth, all flushed with success, little suspected that, in bowing them his acknowledgments, he was taking leave of them and worldly society. Gifted with much talent, assured of worldly success, and favored by society, he was going to renounce the brilliant career that lay before him in the world to become a priest. None of the audience, except his father, suspected that he was about to turn his back on the pomps and pleasures of the world to give himself entirely to the service of God in a monastery. None of them knew that he was going to cast off all that finery of dress to clothe himself in the poor habit of a Passionist. None of those who so joyfully cheered and applauded knew that the day of his triumph was the eve of his departure from them. When Francis parted with his friends that night, and said good-bye to them, they thought that he was only going for a holiday. The next day he left home and set out for the Passionist Novitiate at Morrovalle, in the province of Macerata.